In zijn boek Praktijkgericht opleiden - al doende leren in de beroepspraktijk beschrijft Jan Willem van den Boogert hoe je leert van ervaringen:

Van ervaren naar leren

Kenmerken van een ervaring

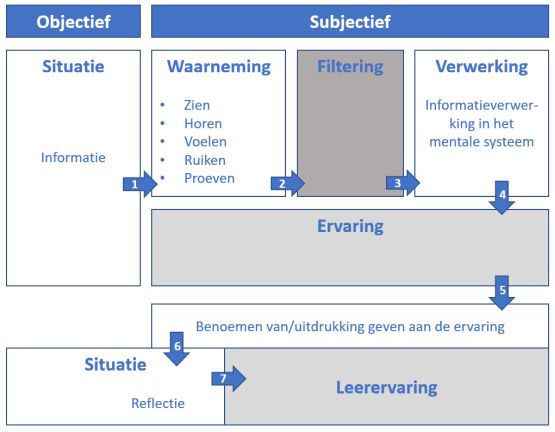

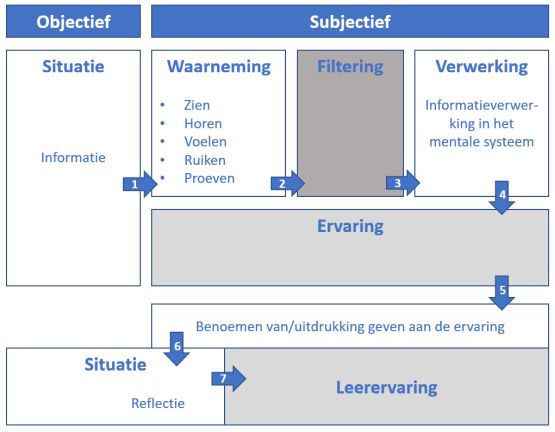

Met een ervaring bedoelen we hier: een ik-beleving in een situatie met een begin- en een eindpunt in tijd. Dit 'beleven' kan inhouden dat we een actieve rol spelen in de ervaring, maar het kan ook betekenen dat we iets waarnemen, en dat andere mensen actief zijn. Ook in dat geval beleven we iets. Als we kijken naar een gebeurtenis buiten onszelf, zijn we bijvoorbeeld geïnteresseerd, geraakt, blij of worden eigen associaties opgeroepen. Den maar aan een gesprek dat u kunt waarnemen, een voordracht van iemand of een film waarnaar u kijkt op tv.

Een ervaring is zoals gezegd een ik-beleving, ofwel een 'subjectieve beleveing' naar aanleiding van een situatie. Deze situatie noemen we een 'objectief feit'. Wanneer we deze situatie beleven, geven we er een eigen betekenis aan. De situatie kan samen met anderen (andere 'ikken') ervaren worden, dat wel, maar voor ieder zal de ervaring anders zijn. Dat blijkt wel als we uitwisselen met elkaar anders zijn. Dat blijkt wel als we uitwisselen met elkaar hoe we een situatie hebben beleefd. Hoe verschillend kan dit zijn!

Een ervaring ontstaat in ons bewustzijn door interactie tussen onze zintuigen en ons mentale systeem.

(...)

Ons hele leven is opgebouwd uit ervaringen. Aan veel ervaringen besteden we geen aandacht. Je kunt ook niet anders. Je bewustzijn zou overvoerd raken als je aandacht zou besteden aan alle ervaringen die je dagelijks opdoet. Vandaar dat we filters hebben, waarmee we vele waarnemingsprikkels uitfilteren.

Aan andere ervaringen besteden we wel aandacht. Welke? Waarom? Per persoon zal deze vraag verschillend beantwoord worden, want ieder is wat dat betreft verschillend.

Van ervaring naar leerervaring

Achteraf aandacht besteden aan een ervaring is te vergelijken met een stukje film terugkijken. Een film waarin je zelf geacteerd hebt en die je hebt opgenomen. Of een film waarin je niet geacteerd hebt, maar die je wel hebt opgenomen.

(...)

Om een ervaring als leerervaring te benutten is het dus van belang dat de lerende op een voor hem of haar belangrijke ervaring inzoomt, zodat deze ervaring als leermateriaal gebruikt kan worden.

We leren veel van eigen ervaringen, doorgaans meer dan uit boeken, ook al zijn voorbeelden in het boek nog zo herkenbaar en treffend. Eigen materiaal heeft een dimensie die van grote waarde is voor leren: de relatie met de eigen emotie.

Bron: Praktijkgericht opleiden - al doende leren in de beroepspraktijk, Jan Willem van den Boogert

Taakanalyse

Definitie

...

Terminologisch heeft men het in professionele contexten niet alleen over leerdoelen, competenties, ... maar dikwijls ook over standaarden ('standards').

In formele instructiesettings staat vooral de analyse van kennisdomeinen en vakken centraal. Bij bedrijfsopleidingen staat vooral een job-analyse (functie-analyse) voorop, naast de concrete taken die een werknemer in die job uitvoert. Rowland en Reigeluth (1996) omschrijven taakanalyse als volgt:

"Het proces waardoor men beter begrijpt wat nodig is voor het uitvoeren en leren van een bepaalde taak, een vaardigheid, een procedure, of van het hanteren van een kennisgebied. (...) Taakanalyse kan ook helpen bij het bepalen van factoren zoals de omgeving waarin de taak het best uitgevoerd, het kritische karakter van de taak, typische fouten bij taakuitvoering en de gevolgen van goede en slechte taakuitvoering."

Vijf doelen staan voorop bij een taakanalyse: taken inventariseren, taken beschrijven, taken selecteren voor instructie, taken ordenen voor instructie (inclusief subtaken) en taken analyseren volgens inhoudsdomeinen. Een taakanalyse kan ook bekeken worden vanuit twee aparte perspectieven: (1) een gedragsmatige taakanalyse die helpt om alle noodzakelijke concreet observeerbare gedragingen in kaart te brengen en te ordenene met een flowchart, en (2) de cognitieve taakanalyse. Die laatste helpt om de onderliggende voorkennis in kaart te brengen. Dit helpt rekening te houden met de niet-observeerbare gedragingen ('overt behaviour').

Bron: Onderwijskunde als ontwerpwetenschap - van leren naar instructie, Martin Valcke (Deel-2)

Doel van de taakanalyse

Wil de ontwikkelaar een ontwerp kunnen maken voor een functie- of taakgerichte opleiding, dan zal hij een duidelijk beeld moeten hebben van de functie of taak waarvoor opgeleid moet worden. De taakanalyse is een hulpmiddel om dat noodzakelijke beeld te krijgen. Een taakanalyse is een specificatie van zowel waarneembaar als niet waarneembaar gedrag dat noodzakelijk is voor de uitvoering van ten taak of cen functie. Als we het woord functie gebruiken staat dit voor de verzameling van hoofdtaken, (deel)taken, taakelementen en handelingen die een medewerker in de organisatie uitvoert of behoort uit te voeren. Die indeling sluit aan bij de begripsomschrijving die Davies (1978, p. 52) en Romiszowski (1981) geven bij het woord functie. Is de functie bijvoorbeeld die van verpleegkundige, — dan is een van de hoofdtaken het toedienen van medicijnen; — een (deel)taak is het toedienen van een insuline-injectie; — een taakelement is het berekenen van de te injecteren hoeveelbeid (in ml) insuline om het gewenste aantal Internationale eenheden (in i.e.) van die stof toe te dienen; — een handeling is het vullen van de injectiespuit.

Door het algemene opleidingsdoel en de geformuleerde opleidingsbehoefte of opleidingsnoodzaak wordt aangegeven hoe omvangrijk de taakanalyse moet zijn: alle hoofdtaken uit een functie, slechts een hoofdtaak, of slechts een of enkcle (deel)taken. In de praktijk worden taakanalyses voor een groot aantal doelen gebruikt: bijvoorbeeld om selectiecriteria vast te stencil, taakwaardering te berekenen, reorganisaties voor te bereiden, om een leidraad bij beoordelingsgcsprekken samen te stellen of om opleidingsdoclen te formuleren.

Het doel van een opleidingskundige taakanalyse kan als volgt worden geformuleerd:

— het verzamelen van informatie over taken, op basis waarvan het mogelijk is concrete leerdoelen voor het opleidingsprogramma te formuleren;

— het vastleggen van de inhoud van ten functiegerichte opleiding;

— het produceren van een document op grond waarvan de opdrachtgever toestemming kan geven voor het verder ontwikkelen van een opleiding.

Davies (1978) formuleert de volgende doelen:

— het beschrijven van de taak die de cursist moet leren;

— het bepalen van de voor die taak vereiste gedragingen;

— het vaststellen van de condities waaronder die gedragingen voorkomen;

— het bepalen van een criterium voor ten aanvaardbare prestatie.

Tracey (1971) geeft de volgende doelen aan:

Het verschaffen van informatie over

— de inhoud van de taak;

— hoe de taak uitgevoerd wordt;

— waarom de taak uitgevoerd wordt;

— hoe de taak samenhangt met andere taken;

— de condities waaronder de taak uitgevoerd wordt;

— de criteria waaraan de uitvoering van de taak getoetst wordt;

— de frequentie van de taak;

— de gevaren die met de taak samenhangen;

— de gereedschappen, hulpmiddelen, materialen en dergelijke die bij de uitvoering gebruikt worden.

Deze informatie dient ertoe om:

— leerdoelen te formuleren;

— vereiste vaardigheden, kennis en persoonskenmcrken vast te leggen;

— het vooropleidingsniveau te bepalen;

— een basis te verschaffen voor het ontwerp van (vaardigheids)toetsen.

Romiszowski (1981) omschrijft het doel van een taakanalyse als volgt: Functie- (of taak-)analyse is een hulpmiddel in het ontwikkelproces waarmee leerdoelen vastgesteld kunnen worden in die situaties waarin de uiteindelijke doelen betrekking hebben op het vervullen van een specifieke functie.

(...)

Methoden om informatie te verzamelen:

1. Documentenstudie

2. Observatie

3. Individueel interview

4. Groepsinterview

4.1 Jury van experts

4.2 Focusgroepen

5. Enquete

6. Critical Incidents en

7. Zelf het werk uitvoeren

Bron: Kessels, J. W. M., & Smit, C. A. (1985). B1.3 Taakanalyses. Handboek Opleiders in Organisaties. No. 4, 1–38.

Task Analysis in Instructional Design

A task analysis is a systemic collection of data about a specific job or group of jobs to determine what an employee should be taught and the resources he or she needs to achieve optimal performance (DeSimone, Werner, Harris, 2002).

(...)

The following must be captured during this step of the Analysis Phase:

- Conditions: Tools or equipment needed and the environment the task is performed in.

- Performance Measure: How well must it be performed? Note that this sub-step is discussed in more detail in the next step, Build Performance Measures.

- Frequency: How often is the task performed (hourly, daily, weekly, etc.)?

- Difficulty: Use a standard scale, such as from one to five.

- Importance: What place of importance is this task as compared to the performer's other tasks?

- Steps: Logical steps for performing the task.

Bron: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/isd/tasks.html

Task analysis is considered the most critical part of the instructional design process (Jonassen, Hannum, & Tessmer, 1999). The analysis solves three problems for the designer:

- It defines the content required to solve the performance problem or alleviate a performance need. This step is crucial because most designers are working with unfamiliar content.

- Because the process forces the subject-matter expert to work through each individual step, subtle steps are more easily identified.

- During this process, the designer has the opportunity to view the content from the learner’s perspective. Using this perspective, the designer can often gain insight into appropriate teaching strategies.

Jonassen et al. (1989) have identified 27 different task analysis procedures that instructional designers can use to define the content for an instructional package. Selecting the best or most appropriate technique depends on a number of factors, including the purpose for conducting the task analysis, the nature of the task or content, and the environment in which the task is performed.

The terminology associated with topic and task analysis is often confusing. The instructional design literature frequently refers to the process of analyzing content as task analysis. Specific analysis procedures also go by a host of names. Some individuals refer to task analysis as a specific procedure for defining psychomotor skills, which leads to further confusion. The term content analysis is also confusing. Some researchers use this term to describe a methodology for analyzing text materials. Instructional designers use content, topic, or subject-matter analysis to define knowledge or content related to the instructional problem. In this lesson, we refer to task analysis as the collection of procedures for defining the content of an instructional unit.

Bron: https://sites.google.com/site/pnusicte03/lesson-9---task-analysis

How to Conduct a Task Analysis

Task analysis is another step in the analysis and objective setting process. Task analysis occurs after the needs assessment and the problem to be addressed by the instructional design has been identified.

Purpose

The purpose of the task analysis is to determine the content that will make up the instruction and to also determine in what order the content will appear.

The Morrison, Ross, Kemp approach to instructional design states that the task analysis answers solves three problems for the ID:

- What content is required for the learning to take place.

- The identification of subtle steps.

- The ID gains insight into the learner's perspective.

Gagne describes task analysis as a series of procedures performed by the instructional designer in order to gather information needed for the instruction.

Methodology

There are a number of approaches to task analysis, and the specific approach taken by the ID will vary based on what type of learning is being developed.

The Morrison, Ross, and Kemp (MRK) method says that the goals that are derived from the needs assessment and the analysis of the learner, specifically what knowledge and background the learner has, influence the content that is required for instruction. This information is the starting point for the ID, in developing objectives.

This approach states that there are three methods for task analysis:

(1) Topic analysis: Topic analysis works similarly to creating an outline, beginning with major information and working down to secondary information. A topic analysis provides information on the content that will make up the learning, as well as its structure. The content can be procedures, skills, facts, concepts, rules, or principles.

(2) Procedural analysis: A procedural analysis aims to identify steps that make up tasks. In this part of the task analysis, the ID will usually work with a subject-matter expert and walk through the steps in the procedure, in as close to the "real-world environment" as possible.

(3) Critical incident method: The critical incident method uses an interview format, wherein the instructional designer interviews the subject-matter expert to determine what skills and knowledge are required to complete the task.

The ID will use the three methods, and the information gathered from all three methods is compiled and used by the ID to write the tasks in the instruction.

Bron: https://www.webucator.com/tutorial/instructional-design/analyzing-objective-setting.cfm

Task analysis is a crucial part of any instruction as it determines what skills and knowledge ought to be taught, the objectives of the learning and the relevant performance assessments and evaluation. However, not all instructional design models or frameworks discuss task analysis; rather, most instruction design is based on assumptions or inspiration.

Without conducting task analysis, instruction faces the risk of falling apart when implemented, not achieving its intended learning outcomes or not meeting the needs and expectations of learners.

Task analysis is sometimes referred to as content analysis or learning task analy-sis in different approaches, but the central tenet is about determining the design of the tasks or of the learning content of the instruction.

For instance, Morrison, Ross and Kemp (2004) used three different techniques for analysing content and tasks: topic analysis, procedural analysis and the critical incident method.

When conducting topic analysis, the instructional designers determine the content and the structure of the content components. Steps that are required to complete the tasks are identified during procedural analysis, while using a critical incident method which predominantly relies on interviews helps the instructional designer to elicit information about the conditions that allow the learner to successfully complete the tasks or which prevent them from completing the tasks.

Smith and Ragan (2005) on the other hand offered a practical approach to conducting task analysis as they considered the process of task analysis as the process of transforming goal statements into a form that can be used to guide subsequent design. Jonassen et al. (1999) provided a more comprehensive view and approach to task analysis. In their book, the authors classified various task analysis methods into the broad categories of job, procedural and skill analysis methods, instructional and guided learning analysis methods, cognitive task analysis methods, activity-based methods and subject matter/content analysis methods.

Bron: Instructional Design Principles for High-Stakes Problem-Solving Environments, Chwee Beng Lee, José Hanham, Jimmie Leppink

Van taakanalyse naar leerdoelen

Het resultaat van de taakanalyse levert de informatie die nodig is voor de leerdoelenformulering. De gehele activiteit bij het analyseren van taken is er immers op gericht om informatie te verzamelen waarmee de volgende vragen kunnen worden beantwoord:

- Welke vaardigheden (psychomotorisch, sociaal of cognitief) en welke kennis, inzichten en welke houding of instelling zijn nodig om de onderhavige taak te kunnen uitvoeren.

De analysetechnieken leveren deze noodzakelijke informatie om de inhoudscomponent van de leerdoelen te kunnen vaststellen.

(...)

- Documentensutide;

- Observatie;

- Individueel interview;

- Jury van experts;

- Focusgroepen;

- Critical incidents;

- Zelf-het-werk-uitvoeren;

- Adoptie;

- Vergelijkingsanalyse;

- Simulatie;

- Enquête.

(...)

Een voorbeeld van een analyseschema is:

- Werkzaamheden (Wat?)

- Werkwijze (Hoe?)

- Hulpmiddelen (Waarmee?)

- Kwaliteitseisen (Normen?)

- Motivering (Waarom?)

- Aandachtspunten (Denk aan?)

Vierfasenleermodel ('bewust bekwaamwordingsproces')

Definitie

Model dat beschrijft via welke vier fasen iemand leert.

Vierfasenleermodel

Ontwikkeld door Noel Burch van US Gordon Training International Organisation (en wordt vaak ten onrechte toegeschreven aan Maslow)

Zie ook:

Alias: hiërarchie van competentie, competentieladder, vierfasenmodel van competentie, bewust bekwaamwordingsproces

Four stages of competence

In psychology, the four stages of competence, or the "conscious competence" learning model, relates to the psychological states involved in the process of progressing from incompetence to competence in a skill.

Management trainer Martin M. Broadwell described the model as "the four levels of teaching" in February 1969.[1] Paul R. Curtiss and Phillip W. Warren mentioned the model in their 1973 book The Dynamics of Life Skills Coaching. The model was used at Gordon Training International by its employee Noel Burch in the 1970s; there it was called the "four stages for learning any new skill". Later the model was frequently attributed to Abraham Maslow, incorrectly since the model does not appear in his major works.

The four stages are:

(1) Unconscious incompetence

The individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not necessarily recognize the deficit. They may deny the usefulness of the skill. The individual must recognize their own incompetence, and the value of the new skill, before moving on to the next stage. The length of time an individual spends in this stage depends on the strength of the stimulus to learn.

(2) Conscious incompetence

Though the individual does not understand or know how to do something, they recognize the deficit, as well as the value of a new skill in addressing the deficit. The making of mistakes can be integral to the learning process at this stage.

(3) Conscious competence

The individual understands or knows how to do something. However, demonstrating the skill or knowledge requires concentration. It may be broken down into steps, and there is heavy conscious involvement in executing the new skill.

(4) Unconscious competence

The individual has had so much practice with a skill that it has become "second nature" and can be performed easily. As a result, the skill can be performed while executing another task. The individual may be able to teach it to others, depending upon how and when it was learned.

Bron: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_stages_of_competence

Understanding the Conscious Competence Ladder

Noel Burch, an employee with Gordon Training International, developed the Conscious Competence Ladder in the 1970s.

The model highlights two factors that affect our thinking as we learn a new skill: consciousness (awareness) and skill level (competence).

According to the model, we move through the following levels as we build competence in a new skill:

- Unconsciously unskilled – we don't know that we don't have this skill, or that we need to learn it.

- Consciously unskilled – we know that we don't have this skill.

- Consciously skilled– we know that we have this skill.

- Unconsciously skilled – we don't know that we have this skill, but we don't focus on it because it's so easy.

Bron: https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newISS_96.htm

The Four Stages for Learning Any New Skill

No matter what new skill we decide to learn, there are four learning stages* each of us goes through. Being aware of these stages helps us better accept that learning can be a slow and frequently uncomfortable process.

Stage 1 – Unconsciously unskilled. We don’t know what we don’t know. We are inept and unaware of it.

Stage 2 – Consciously unskilled. We know what we don’t know. We start to learn at this level when sudden awareness of how poorly we do something shows us how much we need to learn.

Stage 3 – Consciously skilled. Trying the skill out, experimenting, practicing. We now know how to do the skill the right way, but need to think and work hard to do it.

Stage 4 – Unconsciously skilled. If we continue to practice and apply the new skills, eventually we arrive at a stage where they become easier, and given time, even natural.

*This Learning Stages model was developed by former GTI employee, Noel Burch over 30 years ago.

Bron: Learning a New Skill is Easier Said Than Done, Linda Adams

Leren en transfer bewerkstelligen

Leren is komen tot effectiever gedrag. Tijdens leerprocessen doorloopt de ge-coachte de cyclus van onbewust onbekwaam (bijvoorbeeld: ik weet niet dat ik defensief reageer op feedback) tot onbewust bekwaam (Ik reageer adequaat op feedback en realiseer me niet eens dat Ik dat doe). Het gaat er dus om dat de gecoachte zo bekwaam wordt in bepaald gedrag, dat het hem soepel en natuurlijk afgaat. Die bekwaamheid Is wat ons betreft een mix van weten, kunnen, willen, durven en zijn. Afhankelijk van het leerdoel zal het accent in meer of mindere mate op bepaalde aspecten liggen.

Voor een geslaagde afloop van het coachtraject is het in praktijk brengen van het geleerde in de dagelijkse werksituatie van groot belang. Doen Is de toets van alle coaching: zo krijgt de gecoachte zicht op het resultaat, en dit resultaat beklijft beter. Dat beklijven is voor ons overigens het verschil tussen leren en transfer bewerkstelligen: Iets leren wil nog niet zeggen dat het geleerde beklijft of toepasbaar is. Dat is wel het geval bij transfer.

Bron: Hoe-boek voor de coach, Joost Crasborn

From unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence

A competent professional has well developed knowledge, skills and attitudes. One well known and useful model (sometimes referred to as the conscious competence learning model, the conscious competence matrix or the conscious competence ladder) describes the journey that people make when learning something new from 'Unconscious Incompetence to Unconscious Competence'.

The origins of the model are unknown and it has the following four steps.

1 Unconscious incompetence — this is where most learners start. They are unaware of their lack of knowledge and skill and, put simply, they do not know what they do not know.

2 Conscious incompetence — as the learner progresses they become much more aware of their limitations and start to recognise what they do not know and cannot do.

3 Conscious competence — as the learner continues to move forward, they become more knowledgeable and skilled and begin to apply their learning. Typically, the learner does this in a deliberate step by step way.

4 Unconscious competence — by this point the learner can perform well in their work without much conscious thought, as their knowledge, skills and attitudes become embedded in their practice.

Bron: The Reflective Practice Guide - an interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection, Barbara Bassot

Maslow: (on)bewust (on)bekwaam

In 1954 heeft Maslow vier fasen onderscheiden in het zich eigen maken van nieuwe kennis, vaardigheden of competenties.

In de eerste fase is de leerder onbewust onbekwaam, dat wil zeggen hij is zich niet bewust van een hiaat in kennis, niet bewust van het feit dat hij iets niet beheerst. Hij is zich er niet van bewust dat zijn gedrag niet effectief is in een bepaalde situatie.

De lerende kan er zelf bewust van worden, dat hij iets mist en moet bijleren, ook een ander kan hem hierop wijzen. Als dit gebeurt, dan komt hij in de tweede fase, hij is bewust onbekwaam: hij weet dat hij iets mist en moet bijleren. Hij weet alleen nog niet precies wat en hoe. Als hij hiernaar op zoek gaat en gaat oefenen, dan komt hij in de derde fase: hij is bewust bekwaam. Hij is bewust bezig zich de gewenste kennis, vaardigheden of competenties eigen te maken en zo ‘bekwaam’ te worden. Oefening baart kunst en op het moment dat hij de nieuwe kennis, vaardigheden of competenties laat zien zonder dat hij zich ervan bewust is, dan is hij onbewust bekwaam. Hij is niet meer bezig met de nieuwe kennis, denkt er niet meer over na, maar laat het automatisch zien, zonder daar zijn best voor te doen.

Sinds Maslow zijn deze fasen – en bijbehorende termen – nog steeds actueel en relevant en bieden ze houvast in het denken over leren en gedragsverandering. Ook voor begeleiders van leerprocessen en veranderingsprocessen zijn deze fasen relevant: iedere fase vraagt om een andere manier van aansturen of begeleiden.

Bron: Maslow: (on)bewust (on)bekwaam

Conscious competence learning model

Several claims of original authorship exist for the 'conscious competence' model's specific terminology, definitions, structure, etc., as we recognize it today. The most notable claims are as follows, among which the evidence showing Martin M Broadwell as originator seems to be the earliest.

•For many years the US organization Gordon Training International has claimed a major role in defining the theory and and promoting its use since the 1970s.

•Separately, a 1974 technical personnel paper, 'Conscious Competency -The Mark of a Competent Instructor', effectively asserts creation/definition of the concept and basic ('conscious competence') terminology by its author, W Lewis Robinson, an industrial training executive.

•And in August 2013 I was informed (thanks Earl L Wiese, Jr) of an earlier description of the modern-day 'conscious competence' model, featured in the 'Teaching for Learning' article by Martin M Broadwell, dated 20 February 1969, in The Gospel Guardian, an American Christian periodical published from the 1950s-1970s.

Bron: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5569e19fe4b02fd687f77b0f/t/5aad8499352f533ca549cc94/1521321113919/conscious+competence.pdf

![]()