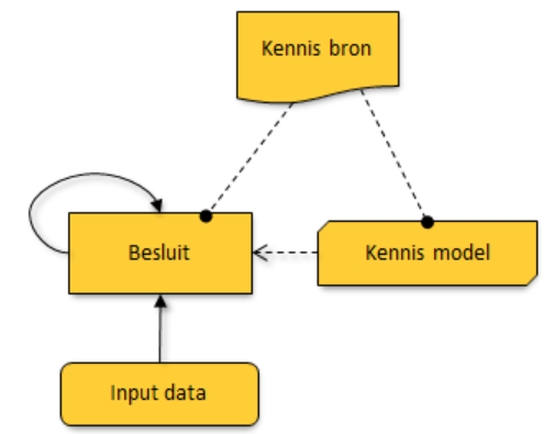

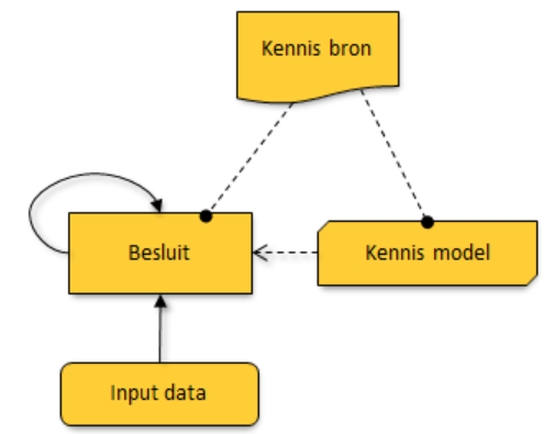

Eén van de modellen binnen het Novius Bedrijfsontwerp is het beslissingsmodel:

Beslissingsmodel

Wat

Een beslissingsmodel specificeert de actie die genomen moeten worden wanneer aan bepaalde condities voldaan wordt. Er zijn momenteel 2 scholen voor het modelleren van beslissingen: DMN (Decision Model & Notation) en TDM (The Decision Model). In deze stijlgids hebben wij gekozen voor DMN omdat deze net als de andere talen in deze stijlgids door de Object Management Group wordt beheerd.

Waarom

Besluiten sturen gedrag in de organisatie. Door de besluiten expliciet te maken worden deze objectiever en het resulterende gedrag voorspelbaarder.

Besluit

Een besluit is de activiteit om aan de hand van een kennis model en input data een beslissing te nemen.

Kennismodel

Een kennismodel is een bedrijfsregel, beslissingstabel of analysemodel aan de hand waarvan een besluit gemaakt kan worden.

Input data

Input data is de data die als input wordt gebruikt bij het nemen van een besluit.

Kennisbron

Een kennisbron is de bron waar een besluit of het kennismodel zich op baseert (zoals wet- en regelgeving, beleid,richtlijnen,productvoorwaarden, etc.)

Kennisrelatie

Een kennis relatie is de aanroep van een kennis model voor het nemen van een besluit.

Informatie-relatie

Een informatierelatie is het ophalen van inputdata, of output van een ander besluit, als input voor een besluit.

Autoriteit-relatie

Een autoriteit-relatie is de referentie naar een kennisbron waarop een besluit of kennismodel gebaseerd is.

- Een besluit past een kennismodel toe. Een kennismodel wordt toegepast in een besluit.

- Een besluit komt voor uit en is gebaseerd op een kennis bron.

- Een kennis bron is de basis voor een besluit.

- Een kennismodel is gebaseerd op een kennis bron.

- Een kennis bron is de basis voor een kennismodel.

- Een besluit gebruikt inputdata. Input data wordt gebruikt door een besluit.

- Een besluit gebruikt als input de uitkomst van een ander besluit.

- De output van een besluit is input voor een ander besluit.

Relatie beslissingsmodelen procesmodel

Een beslissingsmodel is een nadere uitwerking van een business rule processtap. Deze relatie wordt expliciet gemaakt door een trace te leggen van het besluit naar de bewuste processtap.Daarnaast komt de input data voor een besluit overeen met een datastore of een dataobject uit het procesmodel.Je kunt ervoor kiezen om alleen DMN objecten te gebruiken in het beslissingsmodel.

Bron: Stijlgids, Novius Bedrijfsontwerp (2018)

Martijn Zoet en Eric Mantelaers onderscheiden in hun artikel Data-analyse nader geanalyseerd zes vormen van data-analyse:

Hoofdindeling van data-analyse

In totaal kunnen zes verschillende typen data-analyse worden onderkend:

- beschrijvende data-analyse;

- verkennende data-analyse;

- inferentiële data-analyse;

- voorspellende data-analyse;

- causale data-analyse;

- mechanistische data-analyse.

In het Engels worden deze zes typen aangeduid als 1. Descriptive, 2. Explanatory, 3. Inferential, 4. Predictive, 5. Causal en 6. Mechanistic.

De meeste eenvoudige analyse is de beschrijvende data-analyse, waarvan het doel is om een samenvatting te geven van de measurements (metingen, waarden, elementen) in de dataset. Voorbeelden hiervan zijn het debiteurensaldo, de omzet, kosten en het aantal klanten.

Een verkennende data-analyse bouwt voort op de beschrijvende data-analyse. Hierbij wordt gezocht naar trends en correlaties, met als doel om hypotheses te formuleren maar nog niet om deze te bevestigen. Een voorbeeld van een dergelijke hypothese is dat debiteuren niet te hoog mogen zijn gewaardeerd.

Het derde type data-analyse, inferentiële data-analyse, is data-analyse gefocust op een gevonden trend, waarvan gevalideerd moet worden of deze trend ook standhoudt buiten de geselecteerde data (steekproef/deelwaarneming). Dit betekent - in termen van de controle - dat een trend is gevonden in de deelwaarneming en dat deze over de gehele dataset wordt getoetst. Dit is de meeste gebruikte analyse wereldwijd, die u zich misschien nog herinnert van de module statistiek (SPSS) in uw opleiding. Een voorbeeld hiervan is dat er een correlatie bestaat tussen omzet en debiteurenstand. Let op: er wordt in dit geval alleen een correlatie aangetoond, maar (nog) geen casueel verband.

De vierde vorm van data-analyse is het voorspellen van een waarde in de toekomst op basis van data (predictive analytics). In dit geval kan de vraag zijn: voorspel de debiteurenstand over zes maanden. Predictive analytics laat puur de voorspellingen zien, maar beschrijft niet waarom de voorspelling werkt.

Een causale data-analyse is gericht op het vinden van de relaties tussen twee metingen. Dit betekent dat wanneer je één meting verandert, je aan kunt geven wat dit gemiddelde voor een andere meting betekent. Bijvoorbeeld: hoe hoger de omzet, hoe hoger de debiteurenstand. Deze analyse laat - gegeven een bepaalde relatie - de gemiddelde impact van de wijziging van de ene meting op de andere zien.

De laatste vorm van data-analyse is de mechanistische data-analyse. Deze vorm van data-analyse zoekt ook naar het effect van één meting op een andere meting. Het verschil met een causale data-analyse is dat een mechanistische analyse zoekt naar hoe het aanpassen van één meting altijd en zeer specifiek leidt tot een voorspelbaar gedrag in de andere meting. Een voorbeeld hiervan - van buiten de accountancy - is hoe het aanpassen van de vleugels van een vliegtuig leidt tot minder weerstand. In de financiële wereld kan gedacht worden aan de harde oorzaak-gevolgrelatie tussen verhoging van het rentepercentage en verhoging van de post rente in de winst- en verliesrekening.

Bron: Data-analyse nader geanalyseerd, Martijn Zoet & Eric Mantelaers

MARGE-model (Arthur Shimamura)

Definitie

...

Alias: ...

The MARGE model

Motivate

We need to be motivated to use energy to keep focused on the learning process.

Attend

Academic learning is a ‘top-down’ activity whereby we consciously attend to the information needed to build our schema from all the stimuli we’re exposed to.

Relate

Shimamura offers numerous biological insights about how we store and connect information through memory consolidation.

Generate

Shimamura suggests: “Think it, say it, teach it! These are the simplest things to do to improve your memory”.

Evaluate

This is the territory of metacognition with a nice metaphor of the prefrontal cortex acting as the conductor of the orchestra of brain functions.

Bron: Shimamura’s MARGE model in six PowerPoint slides

MOTIVATE

We need to be motivated to use energy to keep focused on the learning process. Designed well, motivation can be intrinsic to learning, for example, by generating curiosity, framing new material as a quest to answer big questions, organis-ing ideas within a wider schema, story-telling and asking the 'aesthetic question': "What do you think? How does it make you feel? Why is it good?" "The aesthetic question engages emotional brain circuits and forces us to attend to and organize our knowledge."

ATTEND

Academic learning is a `top-down' activity whereby we consciously attend to the information needed to build our schema from all the stimuli we're exposed to. This is hard so 'mind wandering' is common and teachers need to expect it. Ideally students will conscious-ly attend to the learning goals and consciously make connec-tions - but sometimes an instructor needs grab attention, acting as their students' prefrontal cortex to direct their top-down processing.

RELATE

Shimamura offers numerous biological insights about how we store and connect informa-tion through memory consoli-dation. The practical strategies include deploying elabora-tive-interrogative questioning -asking how and why - using mental images, analogies, constructing concept maps as schematic representations of sets of connected ideas and training students to make notes organised in hierarchical structures.

GENERATE

Shimamura suggests: "Think it, say it, teach it! These are the simplest things to do to improve your memory". He details multiple ways in which our memories are strengthened when we generate information from our memory, not simply restating it but using our own words. If we tell someone what we've learned we can improve our memory by 30-50%. Explained in terms of brain functions, Generate reinforces the widely known retrieval practice concept.

EVALUATE

This is the territory of metacog-nition with a nice metaphor of the prefrontal cortex acting as the conductor of the orchestra of brain functions. There's a problem with the illusion of knowing when we are familiar with information even when we cannot fully recollect it. We stop trying to learn more if we kid ourselves into thinking we already know it. Students should, therefore, be taught to check their understanding using spaced retrieval practice, generating information by explaining their learning to others as a form of self-test.

Bron: https://headguruteacher.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/marge.pdf

MARGE is an acronym for five principles of efficient learning—MOTIVATE, ATTEND, RELATE, GENERATE, and EVALUATE. Each principle embodies it own neural circuitry and psychological properties.

(...)

MARGEis your mnemonic to help you remember the five principles of efficient learning: MOTIVATE, ATTEND, RELATE, GENERATE, and EVALUATE

M is for MOTIVATE

Evolutionarily speaking, we are learning machines—geared to sense our environment, register new experiences, and adapt accordingly. In modern times we have co-opted this survival mechanism to enjoy the pleasures of conversa-tion, television, movies, and other forms of entertainment. Unfortunately, our modern pleasures have become much too passive, as we fail to engage ourselves actively with new learning experiences. Howwemotivateourselves and others is the first principle of MARGE and perhaps the most difficult one to implement. There are times when personal interests make it easy for us to seek new information, such as learning about a favorite topic, activity, or hobby. The trick to moti-vation is to expand the spectrum of pleasure-seeking experiences and push ourselves into new learning situations. Indeed, just enveloping ourselves in a new setting and breaking away from regular habits—particularly those passive ones in front of a television or computer screen—will fully engage our learning machine. Take a walk around unfamiliar terrain and you will motivate yourself to attend, relate, generate, and evaluate.

(...)

A is for ATTEND

We spend our waking moments bombarded by a ca-cophony of sensory signals—sights, sounds, smells, tastes, touches—so much so that it is amazing that we can make any sense of the world around us. Add internal gyrations—feelings and random thoughts—and it becomes evident that our brains require some way of focusing and guiding mental activities.Information overloadis a major obstacle toward efficient learning, and thus our ability toattendto specific thoughts and sensory inputs isessential.

(...)

Memory theorists suggest that our vast storehouse of knowledgeis distributed widely in broad regions of the cerebral cortex as a network of interconnected information. So how does conceptual knowledge get stored in this manner? It is argued that facts and concepts through repeated activationsbecomeintegrated,related,and established as cortical networks through a process called memory consolidation.

By this view, conceptual learning requires (1) PFC activation of pertinent information in working memory, (2) MTL binding of that information, and (3) memory consolidation—that is, reactivating and relating new information into existing knowledge networks stored in the cerebral cortex.This biological framework reinforces the third princi-ple of MARGE—the need to RELATE new information to what we already know. Throughout the learning process it is critical to establish meaningfulchunksofnew infor-mation and relate them to existing knowledge. Yet some-times we need to learn seemingly arbitrary associations that have no inherent meaningfulness, such as remembering a group of terms or names of places. In such cases, it is

23often useful to create your own verbal or visual mnemonic.

(...)

Verbal and visual mediators are effective for arbitrary associations that don't have intrinsic meaning. More important is the need to develop techniques that integratemeaningful facts and concepts into existing knowledge frameworks. An effective way to do this is to apply what I call the 3 C's — categorize, compare, and contrast. While learning new material, say a new term or fact, bring to mind related information that will help you categorize (i.e., catalog) the new information into your existing knowledge base. Learning is facilitated by finding similarities (comparing) and differences (contrasting) between new material and what you already know. While reading this chapter, you might ask, Who is Henry Molaison and why is he important for memory research? Contrast the roles of the PFC and MTL in learning and memory? When you apply the 3 C's, you actively attend to relevant features, reactivate the information, and relate it to your existing knowledge base.

(...)

One technique that draws on the 3 C's is the elaborative-interrogation-mnemonic, in which new learning is accompanied by asking "why" or "how" ques-tions and generating reasonable answers. For example, here are some facts about blue whales abstracted from Wikipedia: Blue whales, the largest animal known to have ever existed, gorge on krill (small shrimp-like creatures) in the rich waters of the Antarctic Ocean before migrating to their breeding grounds in the warmer, less-rich waters nearer the equator.To elaborate on this information consider such questions as,Why do blue whales spend time in the Antarctic Ocean? Why do they migrate to warmer waters near the equator?

The simple act of generating questions and providing answers helps to integrate new facts into your knowledge database. The elaborative-interrogation mnemonic forces you to categorize, compare, and contrast. Another way to reactivate and integrate facts is to de-velop a mental image or better yet a mental movie, such as imagining a huge blue whale feeding on krill amongst glaciers then swimming toward the equator to breed.

You can narrate your movie and create your own documentary of the information. By actively working on your visual production you are mentally organizing conceptsas a meaningful cluster that can be integrated into what you already know. A useful way to introduce new conceptsis to consider metaphors and analogies that connect new schemas to familiar ones. For example, by relating conceptual knowledge to the web-based Wikipedia application, one gains a sense of how human memory can be viewed as a network of organizedfacts and how new information can be added by linking new informationto existing knowledge. Metaphors and analogies work because a new conceptual framework is described with respect to a familiar concept.

(...)

New information must be appropriately organized into existing knowledge for it to be well establishedand easily retrieved in the future. In a classic memory study,6individuals were given two ways to learn a list of 18 min-erals. One group was simply shown the words in a random display and asked to remember them.Another group was shown the words diagrammedas a conceptual hierarchyin which themineralswere grouped into meaningful sub-categories, such as METALS and STONES (see figure).

(...)

We are familiar with the standard method of formatting hierarchical outlines, with Roman numerals indicating the main topic, then capital letters, numbers, and lower case letters referring to subsequent sublevel cate-gories. A partial outline format of the stimulus set of minerals is shown in the figure. Outlines provide an essential means of organizing conceptual knowledge—not unlike how conceptual knowledge should be stored as mental schemas. Keep in mind the hierarchical organiza-tionsof your own knowledge and how new information fits into these frameworks.

(...)

Concept maps9are schematic representations, that can be usefulas study material.They provide a visual schema in which terms are represented as boxed items (nodes), which are linked by arrows (propositions) that define relationships. ... Concept maps can be used to reformulate lectures or textbook chapters into student-generated representations. When constructing concept maps (and hierarchical outline formats) it is best to limit the numbers of outgoing links (arrowsor subcategories) to not more than five (three or four outgoing links per item is optimal). When we use relational memory techniques, such as forming verbal/visual mediators, applying the 3 C's, forming metaphors/analogies, and constructing schematic organizations (outlines, concept maps), we are facilitating memory consolidation and long-term retentionthrough elaboration and reactivation. These methods engage the learner by relating and integrating new information asmeaningful links to existing knowledge. Thus,relate itto make it stick!

Make it Stick: Relate New Information With Existing Knowledge

? Chunk it: Group information as meaningful units.

? Associative it: Consider using acronyms, verbal mediators, and visual imagery.

? Use it: Think about the 3 C's—categoriLe, compare, and contrast.

? Integrate it: Apply elaborate-interrogation mnemonic, and mental movies.

? Relate it: Use metaphors and analogies to link new concepts to prior knowledge.

? Organize it: Construct schematic representations (hierarchical outlines, concept maps).

(...)

R is for RELATE

... From studies of Molaison and other amnesic patients, we have come to appreciate the importance of the MTL in storing event (i.e., "episodic") memories. The pre-frontal cortex (PFC) activates information in the posterior cortex, and the MTL binds this information (lines) as a stored unit. Neuroimaging findings have corroborated the role of the MTL in establishing memory for many kinds of material, including verbal information, scenes, sounds, and faces.

Terms such as relational binding and relational memory have been used to characterize this process, which allows for the rapid linking of activations as a bound set of features—such as binding right now what you're thinking, seeing, hearing, and feeling. It is presumed that this binding process operates continually to provide a stored record of our daily experiences.

Although the MTL is critical for storing episodic memories, conceptual knowledge must be stored outside of the MTL, otherwise amnesic patients wouldn't be able to access their existing knowledge or converse normally. Memory theorists suggest that our vast storehouse of knowledge is distributed widely in broad regions of the cerebral cortex as a network of interconnected information.

So how does conceptual knowledge get stored in this manner? It is argued that facts and concepts through repeated activations become integrated, related, and established as cortical networks through a process called memory consolidation. By this view, conceptual learning requires: (1) PFC activation of pertinent information in working memory, (2) MTL binding of that information, and (3) memory consolidation—that is, reactivating and relating new information into existing knowledge networks stored in the cerebral cortex

(...)

G is for GENERATE

Think it, say it, teach it! These are the simplest things to do to improve your memory. Have you read an interesting news item lately? Listened to a fascinating podcast? Tell someone what you've just learned. Not only will you be engaging in healthy social interchange, you'll remember the information better yourself! Do you want to remember the name of someone you just met? Say the name aloud—"It's a pleasure to meet you Jim"—and it will stick better in your memory. This is the GENERATE-principle of MARGE, and it can improve your memory by 30-50%! When we generateinformation, learned material is re-activated, thus enabling memory consolidation, the brain process that establishes long-lasting conceptual memories.

(...)

E is for EVALUATE

How do you know what you know? Psychologists use the term, metacognition,1to describe the ability to evaluate our own mental processes. If a student comes up after an exam and says, "I don't know why I did so poorly,I thought I really knew the material"—it clearly suggests poor metacognition. Such "illusions of knowing" can stall learning proficiency, because a student would not feel the need to study further if he/she felt that the material was already well learned. The need to evaluate what we know is the fifth principle of MARGE.

(...)

Teachers can encourage the EVALUATE-principle by having students practice retrieving information during class time. Rather than lecturing the whole time, question/answer "retrieval practice" periods should be sprinkled throughout the presentation. The best way to engage students is to offer open-ended questions and call on students to provide answers. Fact-based questions can also be useful to determine if students are paying attention (Can someone tell me the difference between recollection and familiarity?). For large classes, another method is to present multiple-choice questions and have students elicit answers with clickers. Research has shown that the use of clickers in class instills active learning and better memory for class material.

For best results, instructors should keep questions to 4-5 per session and allow 30 seconds for students to answer each question. Between initial learning and exam time, students must engage in multiple retrieval practice sessionsthat involve a combination of generating and evaluating course material. The easiest way to do this is to test yourself by writing down in your own words what you remember froma lecture or homework assignment.

Bron: Shimamura, Arthur, MARGE: A Whole-Brain Learning Approach for Students and Teachers

![]()